AlphaZero

AlphaZero is a landmark result in Artificial Intelligence research: it is a single algorithm that mastered Chess, Go and Shogi having access to only the game rules. And ‘mastered’ here means beating the worlds strongest chess engines (an open source implementation of AlphaZero, Leela Zero, is now the official computer chess world champion ), and easily beating the version of AlphaGo that beat Lee Sedol. It has also achieved some fame in the wider world: it might not have its own documentary like AlphaGo , but it does have its own New Yorker profile !

I implemented AlphaZero for the DeepMind OpenSpiel repository, and this post takes a scenic tour through things that I’ve learnt studying and implementing this algorithm.

The Problem

The AlphaZero algorithm learns to play two-player zero-sum perfect information games like Chess, Go or Tic-Tac-Toe. Before jumping into how AlphaZero learns to play these games, it is important to understand why they are so hard.

To make this discussion more concrete, I will use Python game implementations from DeepMind OpenSpiel . Games can have a result of either a win, draw or loss, represented as $z=\{1,0,-1\}$. If the game result is $z$ for player 1, then it is $-z$ for player 2, a simple property of the games being zero-sum. As an example for using OpenSpiel, let us try answer a highly non-trivial question about chess: if both players take random moves, what proportion of games are drawn?

import random

import pyspiel

def random_move_game(game):

state = game.new_initial_state()

while not state.is_terminal():

random_action = random.choice(state.legal_actions())

state.apply_action(random_action)

return state.rewards()[0]

num_trials = 10 ** 4

game = pyspiel.load_game("chess")

res = [random_move_game(game) for _ in range(num_trials)]

print("Drawn games (%): ", 100 * res.count(0.0) / num_trials)

# Output: Drawn games (%): 84.738

So around $84.7\%$ of games are drawn.

Minimax

Rather than taking a random move, what is the best move? And what game result $z$ would we get if both players took the best moves? A very simple algorithm exists that answers both of these questions: the minimax algorithm . First, the expected game result for a given state is called the value $v$. The idea of the minimax algorithm is to always choose an action that minimizes the maximum value the other player can obtain. We can implement this as a recursive algorithm in a few lines of Python:

def minimax(state, max_player_id = None):

if max_player_id == None:

max_player_id = state.current_player() # 0 or 1 for 2-player game

if state.is_terminal(): # check whether state is a leaf node

return {'action': None, 'value': state.rewards()[max_player_id]}

actions = state.legal_actions()

actions_values = [{'action': a, 'value': minimax(state.child(a), max_player_id)['value']} for a in actions]

if max_player_id == state.current_player():

return max(actions_values, key=lambda x: x['value'])

else:

return min(actions_values, key=lambda x: x['value'])

As a test, lets try it on tic-tac-toe:

state = pyspiel.load_game("tic_tac_toe").new_initial_state()

minimax(state)

# Output: {"action": 0, "value": 0.0}

A value of $0.0$ for the first move tells us that if both players play optimally, the game will always be a draw, which confirms what we know about tic-tac-toe. One more check is to play the minimax agent against a random agent and another minimax agent. The minimax agent should always draw against another minimax agent, but could win or draw against a random agent:

def play_game(game, agent1, agent2):

state = game.new_initial_state()

while not state.is_terminal():

if state.current_player():

action = agent2(state)['action']

else:

action = agent1(state)['action']

state.apply_action(action)

return state.rewards()

def random_agent(state):

return {'action': random.choice(state.legal_actions())}

[play_game(game, minimax, random_agent)[0] for _ in range(10)]

# Output: [1.0, 1.0, 1.0, 1.0, 0.0, 1.0, 1.0, 0.0, 1.0, 1.0]

[play_game(game, minimax, minimax)[0] for _ in range(10)]

# Output: [0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0]

Now we can compute (in finite time) what the best opening move is in Chess, and whether white wins, loses or draws under optimal play:

# don't actually run this: it will basically run forever!

state = pyspiel.load_game("chess").new_initial_state()

minimax(state)

# Output: unknown!

But it is still an

unsolved problem

what minimax(state) returns, because it takes too long!

The reason is that the minimax algorithm needs to traverse the entire

game tree

, and this tree is extremely large for Go and Chess.

Just how long would we expect an algorithm traversing the entire Go and Chess game trees to take? Go has around $2\times 10^{170}$ legal board positions, whilst an upper-bound for chess board configurations is around $\sim 10^{46}$.1 And minimax needs to visit each of these states to compute the best opening move.2 The highest clock speed of any CPU is 8.723 GHz for an overclocked AMD CPU . This means that it can (maximally) do $8.723 \times 10^{9}$ operations a second. Even if it could look at one board position per clock cycle (in practice it will be much lower), it would take $\sim 10^{144}$ billion years for Go and $\sim 10^{19}$ billion years for Chess for the computation to complete! For reference, the universe has only existed for around 14 billion years. If ever there is a hopeless computation, this is it!

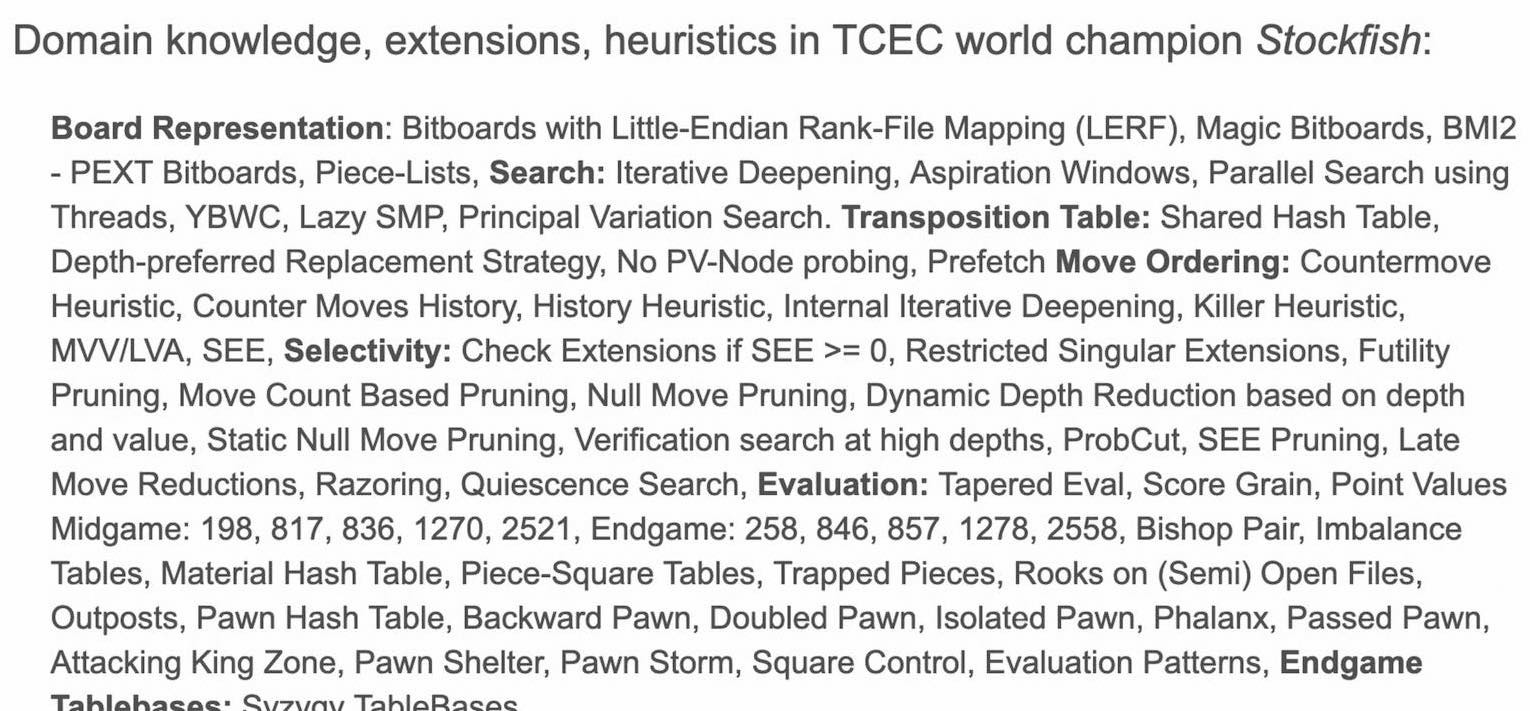

As finding the best move for Chess or Go is impossible, all we can do is find the best move within some computational budget. For Chess, a computer (Deep Blue) already beat the human world champion (Gary Kasparov) in 1996. Computer chess engines have gotten vastly stronger in the 24 years since, with the best of the lot being Stockfish. It uses a large set of Chess-specific tricks and heuristics to only search through the most promising moves:

As we will see shortly, AlphaZero is a vastly simpler algorithm with zero tricks specific to Chess. Yet it is significantly stronger than Stockfish with all of its tricks! This fits into the fortunate trend that learned systems are usually a great deal simpler than the hand-engineered systems they supersede ( “Google’s Jeff Dean has reported that 500 lines of TensorFlow code has replaced 500,000 lines of code in Google Translate." ). And it provides a motivating example for Rich Suttons ‘Bitter Lesson’ :3

The biggest lesson that can be read from 70 years of AI research is that general methods that leverage computation are ultimately the most effective, and by a large margin… Search and learning are the two most important classes of techniques for utilizing massive amounts of computation in AI research. In computer Go, as in computer chess, researchers’ initial effort was directed towards utilizing human understanding (so that less search was needed) and only much later was much greater success had by embracing search and learning.

Monte Carlo Tree Search

AlphaGo, AlphaZero and the previous best Go-playing software (see Crazy Stone ) all use a particular game search strategy called Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS). This avoids having to visit the entire game tree like minimax, but requires two key ingredients, a policy and value function, that we will look at first.

Consider a neural net with learnable parameters $\theta$ that takes as input the game state $s$ and returns two outputs, $(\mathbf{p}, v)=f_\theta(s)$. The policy output $\mathbf{p}$ is a probability vector over all possible actions. This tries to predict the best move to make. The value output $v\in [-1,1]$ is a scalar estimating the outcome of the game in state $s$, $\mathbb{E}[z|s]$.

One obvious way of training such a function would be to learn to imitate expert games. For such games, we have tuples $(s_i, a_i, z_i)$, where $s_i$ is the state, $a_i$ is the action taken by the player in state $s_i$, and $z_i$ is the eventual outcome of the game. This is a simple supervised learning problem: $\mathbf{p}$ should have high probability for $a_i$ (classification) and $v$ should be close to the result $z_i$ (regression). AlphaGo did precisely this procedure as a pre-training step before using reinforcement learning to improve on this. We will see another way shortly.

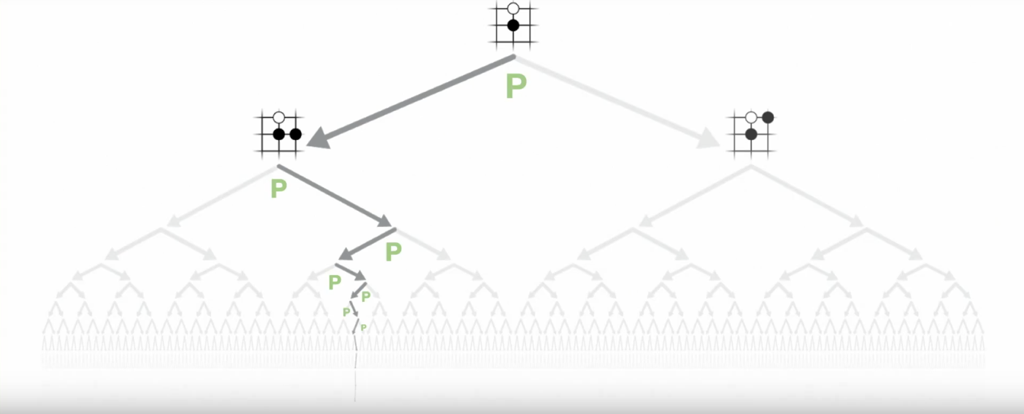

This magic function $(\mathbf{p}, v)=f_\theta(s)$ allows us to dramatically simplify searching the game tree. First, the policy gives us a prior over the best moves. Focusing on the most plausible moves allows us to reduce the breadth of the tree:

Having a value $v$ allows us to reduce the depth of the tree by replacing the actual game result with an estimate of what would have happened if we played to the end:

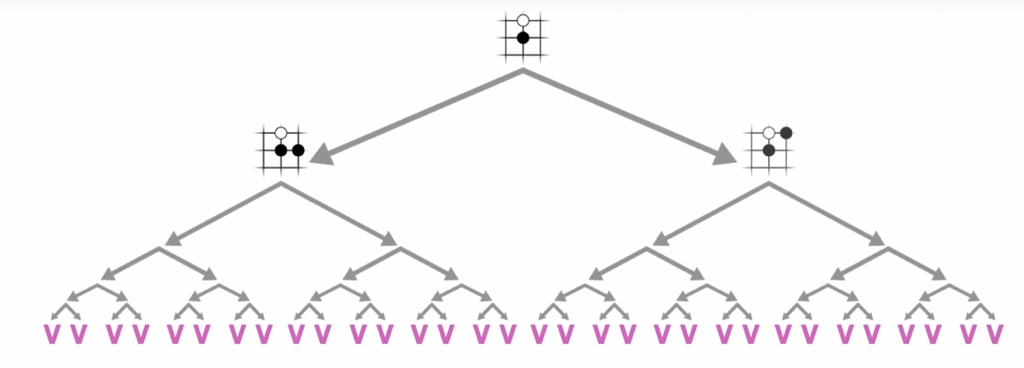

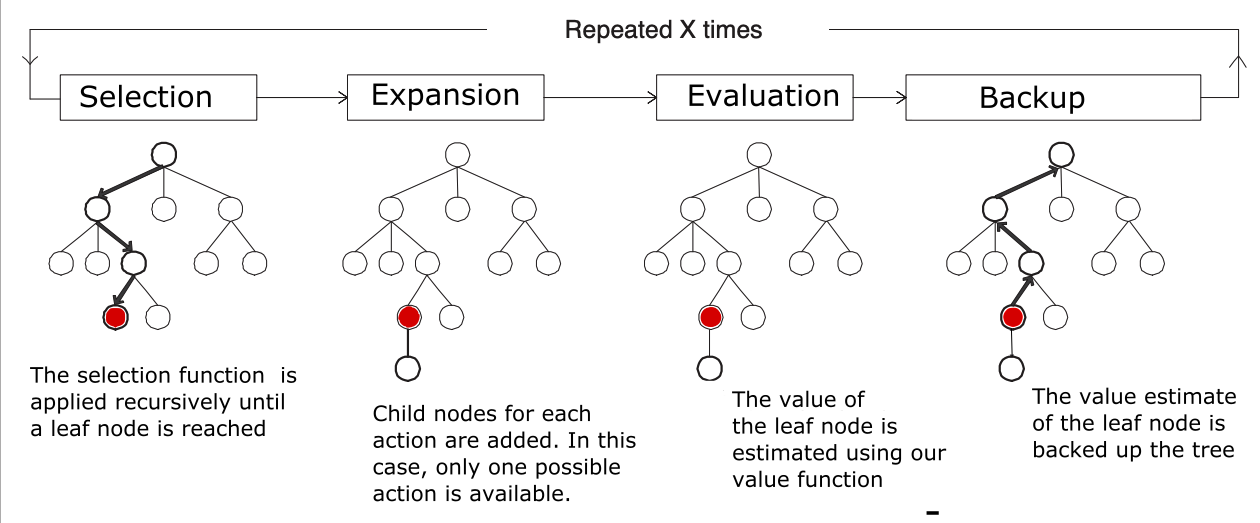

MCTS is the best-known approach to exploring game trees by limiting their depth and breadth using a policy and value function. First, consider a node in the game tree:

class Node(object):

def __init__(self, game_state, prior):

self.game_state = game_state

self.value_sum = 0

self.visit_count = 0

self.prior = prior # real number from policy function

self.children = {} # {action1: node1, action2: node2, ...}

The game is in some state $s$, and we want to know what next move to make. This will be the root node in the search tree, root_node=Node(state_s, None). Then repeat this procedure $N$ times:

Selection. Start at the root

root_node, take actions until a leaf node is reached, which is a node that hasn’t been visited yet (leaf_node.visit_count == 0). How these actions are selected will be explained later.Expansion and Evaluation. If this leaf node is not terminal (i.e. a node where the game has not ended), then add the nodes corresponding to all actions,

leaf_node.game_state.legal_actions()toleaf_node.children. Use the neural net to compute the policy and value forleaf_node.game_state. The policy gives apriorfor each action, used to initialize each child node.Backup (also called Backpropagation). For every node

nodein the path taken to the leaf node, add the value of the leaf nodenode.value_sum += leaf_valueand add a countnode.visit_count += leaf_child_value.

This was repeated 800 times in the original AlphaZero implementation, and then the visit counts for each child in root_node.children were softmaxed, giving a new policy $\pmb{\pi}$ over actions. This new policy is generally better than using the neural net policy $\mathbf{p}$. MCTS can thus be viewed as a policy improvement operator, $\pmb{\pi}=\text{MCTS}(s, f_\theta)$

There is one important detail missing: how to select actions in the Selection step. The key is that we want to balance exploration and exploitation: the node.visit_count tells us how often we’ve tried this action, and we want to choose actions that we haven’t tried too often. And we also want to try the actions we know are best, based on our policy-value function and the results of our search. This could be interpreted as a

multi-armed bandit

problem, for which we have provably optimal methods (eg.

Thompson Sampling

or the

Upper Confidence Bound algorithm

). Indeed, AlphaZero uses a variation of the Upper Confidence Bound algorithm to select nodes.

Further Reading:

- There are some extra details in the AlphaZero-variant of MCTS, for example adding Dirichlet noise to the priors of the child nodes of the root node to

avoid certain pathologies

.

For the full details, see the

run_mctsfunction in the official AlphaZero Python-based pseudocode (see Data S1 on the AlphaZero supplementary materials page for full details. Or this gist ). - For a thorough discussion of MCTS in general, see An Analysis of Monte Carlo Tree Search , S. James et al., 2017.

- A nice blog post on AlphaZero and MCTS by Tim Wheeler

The AlphaZero Algorithm

Now we are ready to write down the remarkably simple AlphaZero algorithm: do the following in a loop:

- Self-play: use the MCTS policy $\pmb{\pi}=\text{MCTS}(s, f_\theta)$ to play against itself. If the game outcome was $z$, then we have (state, MCTS policy, game result)-tuples $\mathcal{D}=\{(s_1, \pmb{\pi}_{1}, z), (s_2, \pmb{\pi}_{2}, -z), (s_3, \pmb{\pi}_{3}, z),\cdots \}$ as our training set. The game result switches between $z$ and $-z$ for each player taking alternating moves. Repeat this for many games.

- Train: the net $(\mathbf{p}_i, v_i)=f_\theta(s_i)$ on $\mathcal{D}$ to minimize the loss $$l = \frac{1}{N}\sum_{i=1}^{N}\left[(z_i-v_i)^2 - \pmb{\pi}_{i}^{\text{T}} \log \mathbf{p}_i\right]+c \|\pmb{\theta}\|^2$$ This loss is just a mean-squared regression loss + a cross-entropy loss along with some L2 weight-regularization.

Thats it! There are two major ideas that underpin this simple algorithm that are worth exploring.

Idea 1: Use MCTS as Training Signal

One of the major problems in reinforcement learning is that the training signal is extremely weak: if you only have the outcome of the game as the signal, the learning algorithm needs to somehow figure out which of possibly hundreds of actions resulted in the single reward at the end of the game. This is known as the credit assignment problem . Compare this with supervised learning, where every example has its own label.

But AlphaZero leverages the fact that it has a perfect model of the environment for games like Chess and Go, which is usually not the case for reinforcement learning problems. This access to a model is what allows one to use MCTS (you can’t search ‘into the future’ if you don’t have a model of the environment). And this gives the fortuitous training signal for every move taken, which is for the net policy to predict the result of a full MCTS search. If learning and search are the only things that scale (as per ‘The Bitter Lesson’ from earlier), then search guided by a learned searcher seems… promising!

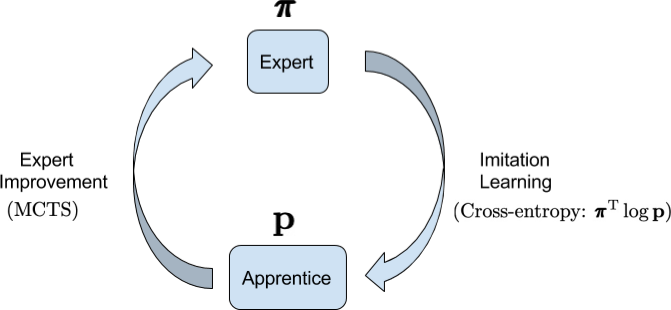

A separate work came up with this idea independently, which they called Expert Iteration : AlphaZero is really a form of Imitation Learning in this picture, where an ‘apprentice’ (the neural net policy) learns by imitating an ‘expert’ (the MCTS policy).

There is also nothing special with using Expert Iteration with the policy: we could do precisely the same with the value estimate, for which MCTS also gives us a better estimate. Using this MCTS value as a training signal for $v$ instead of $z$ was tried successfully for AlphaZero .

One final point about the power of having access to a model: we can easily generate other training signals based purely on consistency requirements of optimal value functions, like Q-learning does. For example, if the current state value is $v_1$, and we take the minimax action using our model and value function, then the value of the state after the opponent has moved is $v_2$. If our value function is optimal, then $v_1=v_2$. Demanding this consistency gives us another signal.

Idea 2: Self-Play

Modern learning algorithms are outstanding test-takers: once a problem is packaged into a suitable objective, deep (reinforcement) learning algorithms often find a good solution. However, in many multi-agent domains, the question of what test to take, or what objective to optimize, is not clear… Learning in games is often conservatively formulated as training agents that tie or beat, on average, a fixed set of opponents. However, the dual task, that of generating useful opponents to train and evaluate against, is under-studied. It is not enough to beat the agents you know; it is also important to generate better opponents, which exhibit behaviours that you don’t know. ~ Balduzzi et al. (2019)

The standard reinforcement learning problem is to find an agent that achieves a high reward against some fixed task. But AlphaZero tries to solve a very different problem: to create a strong Chess or Go playing agent without any immediate feedback on whether it is getting better. Its play needs to generalize against opponents (humans or other machines like Stockfish) that have strategies unknown during training time.

The general problem of creating opponents with diverse strategies for agents to train against in multi-agent reinforcement learning is still an unsolved problem. For example, DeepMinds StarCraft agent AlphaStar was initialized with diverse strategies from human players via imitation learning, rather than trying to learn them from scratch.

But AlphaZero puts a major restriction on the kind of games it can learn to play: the games must be approximately transitive. This means that if some agent A usually beats B, and if agent B usually beats C, then A usually beats C. Compare this to a nontransitive (or cyclic) game such as Rock-paper-scissors . Strategy games like StarCraft are also nontransitive by design: there is no best strategy, as every strategy can be countered by some other strategy. And part of the fun is trying to figure out what strategies your opponent is using with extremely partial information.

But Chess and Go are not like this, as they have a unique best strategy because of their transitivity. And this is critical for AlphaZeros self-play: we will produce a sequence of policy-value nets $(f_{\theta_1}(s), f_{\theta_2}(s), \ldots)$ for every iteration of self-play followed by training. Given that our training ensures that $f_{\theta_{n+1}}(s)$ is a better than $f_{\theta_{n}}(s)$, transitivity gives us that $f_{\theta_{n+1}}(s)$ is also better than all previous nets $f_{\theta_1}(s), f_{\theta_2}(s), \ldots f_{\theta_n}(s)$. Hence self-play is going to produce a sequence of nets that have ever-increasing playing strength!

Note that transitivity is also essential for the popular Elo rating system for games like Chess and Go. This allows one to make a statement such as:

A player whose rating is 100 points greater than their opponent’s is expected to score 64%; if the difference is 200 points, then the expected score for the stronger player is 76%.

Yet transitivity is not enough: if the agent only learns a single opening sequence, and its opponent (ie. itself) does the same, it might completely fail when an unseen opponent challenges it with a completely different opening strategy. Indeed, there are books like “Winning in the Chess Opening: 700 Ways to Ambush Your Opponent” that give weaker players all sorts of dirty tricks and traps to take down a generally stronger opponent.

The solution that AlphaZero takes is to inject noise at all levels of the algorithm to ensure move diversity during training: MCTS is already a noisy search that balances exploration/exploitation, but AlphaZero also adds Dirichlet noise to MCTS, and samples from the MCTS policy for the first 30 moves rather than always taking the most probable move.

Some Practical Details

It is worthwhile providing a flavour of some practical details that have been glossed over so far:

Many board games like Chess or Go are partial-information environments given only the current board position. For example, castling in Chess is only legal if the king and rook have never moved. Or a match can be drawn by the threefold repetition draw rule . All of this information, along with the board position, is encoded in a $N\times N \times M$-dimensional tensor that a convnet can operate on. The exact details are given in the AlphaZero supplementary paper .

$\pmb{\pi}=\text{MCTS}(s, f_\theta)$ is always used to decide on the move. But for the first 30 moves, AlphaZero samples the move from the distribution $\pmb{\pi}$, and then takes the move corresponding to the maximum of $\pmb{\pi}$ past 30 moves. It was found to increase move diversity, which improved performance.

Old and new training data tuples $(s, \pmb{\pi}, z)$ are kept in a replay-buffer of size $10^6$. During training, data is sampled randomly from this buffer, which means that the training is not entirely on-policy .

Limitations and the Future

“Putting these key attributes together produces the informal definition of intelligence that we have adopted: Intelligence measures an agent’s ability to achieve goals in a wide range of environments.” ~ S. Legg (DeepMind co-founder) and M. Hutter (inventor of AIXI ), A Collection of Definitions of Intelligence , 2007

After the success of AlphaGo, DeepMind has gradually managed to generalize AlphaGo’s core ideas (planning with MCTS + deep learning) to increase the range of environments it can master, a necessary condition to eventually “solve intelligence” ):

| Method | Date | Innovation |

|---|---|---|

| AlphaGo | January 2016 | The first algorithm to beat a Go world champion. |

| AlphaGo Zero | October 2017 | Removed the need for supervised training on human expert games before using reinforcement learning and self-play. |

| AlphaZero | December 2018 | All Go-specific details are removed, and trained on Go, Shogi and Chess. Beat the strongest chess computer software, StockFish . |

| MuZero | November 2019 | Drops the requirement of having a model of the environment; learns the model instead. Supports single-agent reinforcement learning. State-of-the-art sample complexity on Atari. |

DeepMind also has a number of other algorithms under its Alpha brand that don’t directly extend the core ideas of AlphaGo, such as AlphaStar for playing StarCraft, and AlphaFold for protein structure prediction.

It is useful to know some of the limitations and restrictions that remain after MuZero, both when considering whether this set of methods can be applied to some problem (AlphaZero has already been applied to problems in quantum computing and chemical synthesis ), and to give inspiration for future research. Here are some limitations:

Perfect Information. Planning

Exploration with a Learnt Model: Environments such as the notorious Montezumas Revenge have extremely sparse rewards: you can almost never get a reward with random play. This is fatal for MuZero, which relies on rewards to build a model of the environment (see Table S1 of the MuZero paper ).

Continuous action spaces. Many domains, such as robotic control, have continuous action spaces. This changes the problem both because there is now an ordering between actions, and because tree-search now has an infinite branching factor. Some work generalizing tree-search to continuous action spaces:

- Monte Carlo Tree Search in continuous spaces using Voronoi optimistic optimization with regret bounds , B. Kim et al, 2020

- A0C: Alpha Zero in Continuous Action Space , T. Moerland et al, 2018

Game Restrictions:

- Transitivity. Cannot be used for StarCraft.

- Symmetry. Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) are example of non-symmetric games, where the opponents have very different roles. Self-play is not possible.

- Zero-sum. Games like Hannabi and Prisoners Dilemma are non-zero-sum.

- Deterministic.

- Sequential. Games like Rock-Paper-Scissors are non-sequential.

- One or two player games. This has been generalized recently to the multiplayer setting .

Comparisons to Human Cognition

System 1 operates automatically and quickly, with little or no effort and no sense of voluntary control. System 2 allocates attention to the effortful mental activities that demand it, including complex computations. The operations of System 2 are often associated with the subjective experience of agency, choice, and concentration. ~ Daniel Kahneman, Thinking, Fast and Slow , Economics Nobel Prize Winner

Some prominent researchers, such as Yoshua Bengio, believe that one of the key problems with current deep learning methods is that they are stuck at being System 1 processes: neural nets take one glance at some input, and immediately return a reaction. They typically can’t make use of more computation to reason and plan, which Bengio believes to be the key to solving one of the greatest limitations of current systems: out-of-distribution generalization.

It is notable that AlphaZero derives its success from using both System 1 (neural net) and System 2 (MCTS) processes, and it leverages this interplay in two very different ways. First, as a way of learning:

When learning to complete a challenging planning task, such as playing a board game, humans exploit both processes: strong intuitions allow for more effective analytic reasoning by rapidly selecting interesting lines of play for consideration. Repeated deep study gradually improves intuitions. Stronger intuitions feedback to stronger analysis, creating a closed learning loop. In other words, humans learn by thinking fast and slow. ~ T. Anthony et al, Thinking Fast and Slow with Deep Learning and Tree Search , 2017

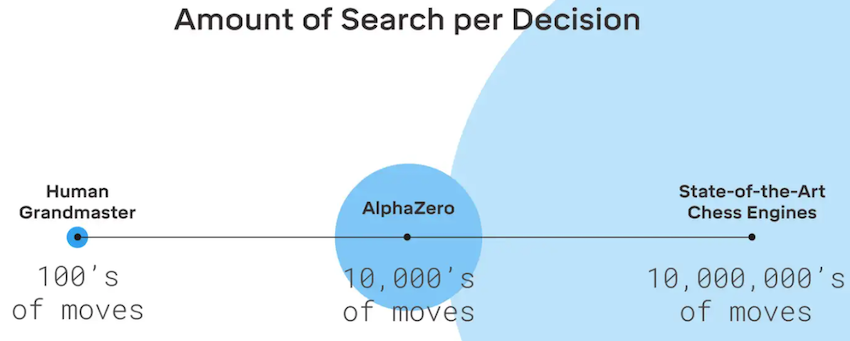

Second, after learning has been done, System 2 can be used to improve on System 1 intuitions by searching and planning. An interesting question is: how important are both of these systems for humans and AlphaZero for games like Go and Chess?

It turns out that System 1 is by far the most important of the two processes for humans. Two Nobel Prize winning economists studied what happened to the playing strength of the then World Chess Champion Gary Kasparov when his time per move was severely restricted. He was given only 30 seconds per move, rather than the 5 minutes he would get in usual tournament time, and had to play many opponents simultaneously so that he couldn’t ‘cheat’ by thinking whilst waiting for his turn:

Data from chess experiments show that a chess master might examine 100 branches of the game tree in 15 minutes, an average rate of about $9s$ per branch. De Groot (1946/1978) found that stronger and weaker players examine nearly the same number of branches, but that stronger players select more relevant and important branches… The simultaneous player with only $30s$, say, for a move will have little time for extensive look-ahead search at $9s$ per branch, and will have to depend primarily on recognition of cues to select the right moves.

How much did Kasparovs playing strength decline? It dropped by only Elo 100 points, from 2750 to 2650!

An Elo rating of 2650 is very high, even among grand masters, only a half dozen players in the world equal or exceed that level

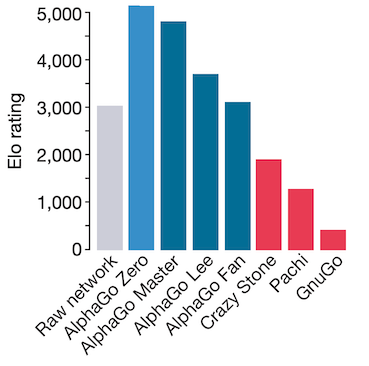

What about AlphaZero without using MCTS? Unfortunately, DeepMind didn’t publish this for Chess, only for AlphaGo Zero:

The raw network policy was around 2000 Elo weaker than the MCTS policy. But it was still as good as AlphaGo Fan that beat the European Go Champion Fan Hui ! One last comparison of interest is how much search AlphaZero uses for versus a human Chess grandmaster:

Lessons for Machine Learning Software

AlphaZero ought to be the poster child for those agitating to move machine learning away from Python due to performance issues.

First, Pythons Global Interpreter Lock (GIL) prevents multithreaded Python code running in parallel. Parallelism is critical for scaling AlphaZero. For example, the primary bottleneck is the hundreds or thousands of policy/value net evaluations needed by MCTS for every move. As is well known, accelerators such as TPUs and GPUs are often an order of magnitude more efficient when processing batched versus unbatched data. To implement MCTS efficiently, the original AlphaGo and AlphaZero implementations used multi-threaded asynchronous MCTS implementations that queue up positions that can be batch-evaluated efficiently on TPUs:

AlphaGo Zero uses a much simpler variant of the asynchronous policy and value MCTS algorithm (APV-MCTS)… Multiple simulations are executed in parallel on separate search threads… Positions in the queue are evaluated by the neural network using a minibatch size of 8; the search thread is locked until evaluation completes

Orchestrating this efficiently with only the process-level parallelism available in Python might not be possible. In addition, we will run many games in parallel to generate training data. With only process-level parallelism, this large corpus of training data needs to be moved to the training process, usually needing expensive serialization and deserialization. These points imply that the entire AlphaZero algorithm would have to be written in C++.

Second, Python is orders of magnitude slower than C++. Even simple argument parsing can take microseconds , which can be comparable to the time taken to evaluate a neural net on some accelerator. Unlike training a convnet, significant Python application logic is required for doing MCTS: its hard to optimize this without simply reimplementing everything in C++.

Given Pythons slowness, C++ is used to implement all of the games in OpenSpiel, as this is performance-critical. But even then, the overhead of Python and shuttling data between language boundaries can be significant: playing random games of tic-tac-toe is around 3x slower using Python and C++ than using pure Swift, and Kuhn Poker is around 10x slower.4 Profilers and debuggers typically cannot see across language boundaries, making it hard to optimize and debug the entire program.

This has the following practical consequence: for OpenSpiel, there are now two separate implementations of AlphaZero , an easy to understand one in Python that can only be trained on toy problems, and a scalable multi-threaded one purely in C++. The very mission of OpenSpiel is sabotaged by the deficiencies of Python:

Above all, OpenSpiel is designed to be easy to install and use, easy to understand, easy to extend (“hackable”), and general/broad.

This problem is probably responsible for the attempt to create a Swift port of OpenSpiel , which uses Swift for TensorFlow as the deep learning framework:

Swift OpenSpiel explores using a single programming language for the entire OpenSpiel environment, from game implementations to algorithms and deep learning models.

Unfortunately this effort appears to have stalled based on the lack of recent commits.

One of the earliest upper-bounds was derived by Claude Shannon , which was $10^{120}$. ↩︎

There are some tricks such as alpha-beta pruning that can avoid minimax having to visit every state. But it still suffers from exponential tree-branching blowup, and is still completely intractable for Chess or Go. ↩︎

This essay generated heated debate in the ML community, along with many responses, for example from Max Welling. and Rodney Brooks . My two cents: simply throwing more compute at current algorithms is definitely not going to solve intelligence. But fundamentally new algorithms and approaches become available with more compute that will probably supersede whatever algorithms we hand-engineered during this (comparatively) compute-starved era. For example, Rodney Brooks mentions that “for most machine learning problems today a human is needed to design a specific network architecture for the learning to proceed well. So again, rather than have the human build in specific knowledge we now expect the human to build the particular and appropriate network”. But with Google-scale compute, you can simply do an architecture search to find to find a network that outperforms all hand-designed ones, vindicating the Bitter Lesson! Or even evolve individual layers . Similarly with Max Wellings complaints about data-scarce regimes, “The most fundamental lesson of ML is the bias-variance tradeoff: when you have sufficient data, you do not need to impose a lot of human generated inductive bias on your model. You can ‘let the data speak’. However, when you do not have sufficient data available you will need to use human-knowledge to fill the gaps.” But what is special about ‘human-knowledge’? Why can’t we learn better inductive-biases (or priors) via metalearning on vast numbers of datasets and environments if we have enough compute? This approach to building general intelligence has been championed by Jeff Clune , for example. ↩︎

I’m using a 2019 Macbook Pro 15 inch. The benchmark code is below: ↩︎